The family of Norman and Sarah May McLeod moved from the Westerlea farm Condah to the Bunyip Hotel at Cavendish in July 1935. At the time it was necessary to effect the move, Mum was inconveniently in the Hamilton Base Hospital having her eleventh and last child, Little Les. So Dad and Norma were the team that first took on the daunting task of learning how to operate a country pub.

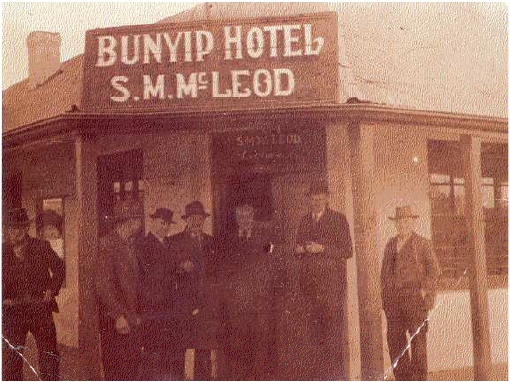

This picture was taken on the first day of the fifteen years plus that the McLeod family spent at the Bunyip Hotel. It shows, from left to right, Howard Docherty, Jim Duncan, two “Goller’s” men, Norman McLeod, a Ballarat Brewery rep and Hughie McLean. This picture was taken on the first day of the fifteen years plus that the McLeod family spent at the Bunyip Hotel. It shows, from left to right, Howard Docherty, Jim Duncan, two “Goller’s” men, Norman McLeod, a Ballarat Brewery rep and Hughie McLean. |

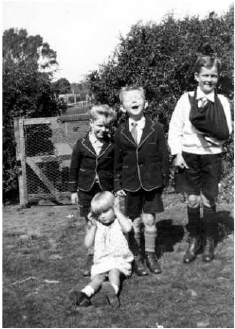

The Hendersons occasionally came to the “Bunyip” to play with us McLeod Kids. I forget their names but recall that they were the children of the local Presbyterian Minister. Left to right are Tom, a Henderson, Rex, another two Hendersons, Dorothy and me. The Hendersons occasionally came to the “Bunyip” to play with us McLeod Kids. I forget their names but recall that they were the children of the local Presbyterian Minister. Left to right are Tom, a Henderson, Rex, another two Hendersons, Dorothy and me. |

The “New” Bunyip was built not long after the McLeods moved in. The sleeping accommodation of the “Old” Bunyip, out of sight to the left of Howard Docherty (Old Doc) in the photo of the old pub, was moved to the back of the new hotel, became bedrooms for the McLeod children and was affectionately known as the Bottom End. Old Doc, incidentally, was well liked by us children – he told enormously exaggerated tales of days gone by and called us, I guess with good reason, “snowy headed young warrigals”. He was an old pensioner who lived alone in a small tin hut on the Balmoral road. In later years he developed cancer. On his discharge from hospital he recuperated for some months as a non-paying guest at the Bunyip. At the time one of the local female mean-spirited wowsers of the village sniffed that this charity by Mrs McLeod was designed to ensure that Doc could still spend his pension on beer at the hotel.

In this photo of the “New” Bunyip, the “Bottom End” can be seen on the right and the Cavendish store across the road on the left. In this photo of the “New” Bunyip, the “Bottom End” can be seen on the right and the Cavendish store across the road on the left. |

Rex, Ian, Tom and Dorothy. Tom had fallen off the bars at school and broken his wrist. My mouth is open and my eyes are shut because the photographer, sister Norma, had told me not to squint. Rex, Ian, Tom and Dorothy. Tom had fallen off the bars at school and broken his wrist. My mouth is open and my eyes are shut because the photographer, sister Norma, had told me not to squint. |

Rex, Norma’s dog Chum, Mum, Les, Dorothy and my cat Ginger, who once made a mighty spring in the kitchen of the “Bunyip” and caught two mice, one under each paw. Rex, Norma’s dog Chum, Mum, Les, Dorothy and my cat Ginger, who once made a mighty spring in the kitchen of the “Bunyip” and caught two mice, one under each paw. |

Yabbiers on the Banks of the Wannon. Yabbiers on the Banks of the Wannon. |

At about the time the photo of the yabbying party was taken, there was held in Cavendish, to raise money for the “war effort”, a Popular Girl Competition. The two contestants were Dorothy McLeod and Kathleen Wright, the latter a daughter of the local carrier, Tom Wright. This well-intended contest had the unfortunate result of splitting the town into two bitterly divided camps. The McLeods were Protestants and the Wrights were Catholics, and a good indication of how much the previous religious bigotries had abated was provided by the fact that the schism was not on sectarian lines. Instead, and despite Tom Wright being an occasional patron at the bar of the Bunyip, the split was between Drinkers and Total Abstainers.

It was customary for the organizers of functions in support of either one of the candidates to seek donations in the form of sweets, cakes, and other fodder from all Cavendish households, irrespective of their allegiance to one or the other of the contestants. I recall how once I was sent to collect a gift of cakes from one of the lady wowsers of the village. As she thrust a cardboard box at me she complained bitterly about how unfair the competition was, because the town drinkers were in the majority and none of them was going to risk upsetting the publican by supporting the opposition to Dorothy McLeod.

When I returned with the offering I relayed the complaint on to my mother. She made no comment, but opened the cardboard box to inspect the cakes. They were hard, black, globular and of about the weight and consistency of the spent cannon balls they so closely resembled. “Hmm”, said Mum. “I’ll put these aside for the next function for Kathleen”.

The decision on the winner of the Popular Girl Competition was based on the amount of money raised for the “war effort” by the girls’ sponsors. Needless to say, Dorothy and the Drinkers won in a canter. Years later, Kathleen Wright would be a bridesmaid at the wedding of Dorothy McLeod and Leo Saligari.

In various stages at the Bunyip Mum had Norma, Betty or Dorothy to help with the housework. From time to time the load would be further lightened by the employment of a maid.

No account of life at the Bunyip, no matter how brief, would be complete without some mention of those redoubtable women. So there follows a Roll Call of Honour of their names, that they be remembered. Not necessarily in chronological order, they were:

Pert “Pepper” Salter, slumbrous-eyed Phyllis Campbell, attractive young local girls Jean and Lorna “Topsy” Duncan, simpleminded Florrie Hall, who had the disconcerting habit of raising her skirts for no other reason than to display her voluminous starched white pantaloons and exclaim “I’m clean! I’m clean!”, generously proportioned Eve O’Donnell and cheeky Doris Dainton. My apologies to any I may have missed.

While the McLeod daughters at the Bunyip helped with household chores, the older sons helped with the bar work. Many a strange conversation occurred in the bar of the Bunyip. For instance this one, oft repeated by brother Donnie, which took place between Dad and Tommy Dark, an old bushman and father-in law to both Donnie and Betty.

Norman – “Did you ever see a snake burn in a bushfire?”

Tommy – “Uh, no.”

Norman – “Nor I, Tom, nor I.”

There are countless other stories of times at the Bunyip that have not yet been recorded. Time and space dictate that that they must remain untold, or perhaps be the subject of a separate, later book. This one has got out of control and badly needs winding down. After another two or three accounts, it will be concluded.

Rex and Snap Rex and Snap |

Les on Akanree Les on Akanree |

The entry of Japan into the Second World War caused both Keith and Donnie to volunteer for enlistment in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF). As both were employed in “protected” industries, Keith school teaching and Donnie on the land, neither would have been liable for conscription. The Army noted that Keith was a schoolteacher, assumed (correctly) that he must be bright, and assigned him to Army Intelligence. Both Keith and Donnie served overseas, Keith in the Phillipines and Donnie in New Guinea.

Alan tried to enlist in all of the Armed Services but, because of problems with his feet, all three rejected his applications. So he went to Melbourne to work in No 2 Small Arms Ammunition Factory, Gordon St, Footscray. There he met a young munitions worker from Terang, the delightful Elsie Smith. They married, and started a dynasty of their own.

Betty joined the Womens Australian Auxiliary Air Force [WAAAF]. Tom desperately wanted to join up too but his job as a telegraphist with the PMG’s Department was proscribed as “essential” and he could not obtain an approval to his repeated requests for a release. The wartime experiences of us younger children were restricted to a few school slit trench drills and lessons on how to deal with the incendiary paper leaflets that Japan was apparently expected to drop over the Australian countryside, but never did.

Cpl Keith McLeod Cpl Keith McLeod |

and his brother-in-arms Pte Donald McLeod. and his brother-in-arms Pte Donald McLeod. |

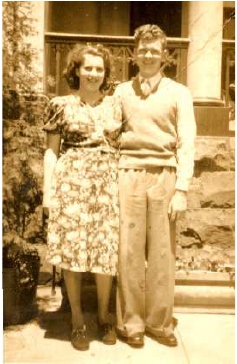

Alan and Elsie McLeod, munitions workers, outside their first home at St Kilda Alan and Elsie McLeod, munitions workers, outside their first home at St Kilda |

Betty McLeod, member of the Women’s Australian Auxiliary Air Force (WAAAF) Betty McLeod, member of the Women’s Australian Auxiliary Air Force (WAAAF) |

Two Telegraph Messengers, Tom McLeod and his mate Jack Graham Two Telegraph Messengers, Tom McLeod and his mate Jack Graham |

The task that none of the wartime telegraph messengers wanted was the delivery to next-of-kin of those dreaded official black-edged telegrams which advised of the death of a loved one.

This photo of Tom was taken in early 1946, so strictly speaking does not belong in the “wartime” section. It is, however, a nice photo and this seems like a good place. As soon as the war was over and manpower restrictions were repealed, Tom joined the Royal Australian Navy. This was a disaster. During his initial training period at HMAS Cerberus Tom, though previously always a happy and well-adjusted boy, suffered a mental breakdown from which he never recovered.

After Donnie’s enlistment in the AIF, he was at first assigned to the American Army base at the Geelong Kardinia Park Football Ground, which had been taken over for that purpose and temporarily renamed Camp Pell. A few Australians were posted there as motor transport drivers on the basis that, unlike the Americans, they were familiar with and wouldn’t get lost in the locality, which included Melbourne. Typically, that theory overlooked the fact that Donnie was a Boy from the Bush who had never before seen the Big Smoke, but, also typically, he somehow found his way around, even though behind the unfamiliar left-hand-driving wheel of a big American Army truck.

After Donnie had been at Camp Pell for a while the American authorities decided to relieve the camp tedium by holding a boxing tournament. Donnie was conscripted to provide a token Australian representation.

It wasn’t the first time that Pte Donald McLeod had worn a pair of boxing gloves. No doubt he would have as a boy sparred with Big Les, and as a teenager he participated in boxing sessions arranged by the Cavendish policeman Constable Bill Cameron. He was a natural fighter who crouched low and weaved in the style of the rough and tough heavyweight Champion of the World, Jack Dempsey. His dual brother-in-law Lloyd Dark told me that “he’s as quick as a cat and hits as hard as an elephant”.

The boxing tournament at Camp Pell was an elimination affair and to the surprise of everyone concerned, including his own, the Australian representative made it through to the light heavyweight final. In that bout he was to meet a black American boxer who was a then current holder of a Golden Gloves trophy, given to an American national amateur boxing champion. Before the finals could be held, however, Donnie was posted by the Australian Army to fight the Japanese in New Guinea. As he was to tell it, “Jeez, I was lucky – I might have been killed!”

This, the last story, is one that was very well told by Phyllis McLeod, the late wife of Donnie.

It was some time in the 1950s and shearing time in the Western District. Dorothy of Doralea had been cooking for the shearers there. Donnie, in Hamilton, decided one evening to check up on how she was faring. He rounded up Rex and they both headed out to Cavendish to see how their little sister was getting on.

When they arrived at Doralea it was to discover that the shearing there was all over and at that very moment a cut-out party was in progress at Ted Saligari’s woolshed, almost next door to Doralea. Donnie decided he was incensed that little Dorothy, instead of being invited to the party, children in tow, had been left home with them and that something should be done about it. He asked Dorothy for a loan of her husband’s Leo’s shotgun.

Donnie and Rex parked Donnie’s car on the side of the road near, but out of sight of Ted’s woolshed, which was on the other side of a slight rise. The two McLeods ascended the rise on foot, Donnie armed with the shotgun and Rex growing more dubious at every step. Nearing the top, the old digger remembered his jungle warfare training and hissed “On your belly!”. They inched their way forward in the dark till they could see the Saligari revellers – Ted, Dudley, Dick, Leo and sundry shearers and their girlfriends, partying around an outside fire.

Donnie raised the double-barrelled shotgun to his shoulder and fired two blasts into the top of the big old gum tree under which the party had been in full swing. Gumnuts rained on the revellers, and a shearer’s sheila shouted “Shit! I’ve been shot!”. Donnie and Rex raced to their car and took off in the direction of Hamilton. “They’ll follow us”, said Rex, now definitely uneasy. “They’ll have guns – those Saligaris are mad”. That last remark seems somewhat out of place, considering the company Rex was keeping that night.

Rex continued to peer anxiously through the rear window. Donnie’s car was a Hillman Minx, not noted for its speed, and before long Rex had cause to cry, “Here they come – they’re gaining on us!” “Not to worry”, said Donnie, “This old fox has got a trick or two up his sleeve yet.” At which, in a valley and with the pursuing cars temporarily out of sight, he pulled into a hollow at the side of the road and switched off the Hillman’s lights. Almost immediately the tightly-knit convoy of Saligari cars and utes roared past. Donnie, in no such hurry, pulled back onto the bitumen and, lights on, leisurely followed them into Hamilton. On the following day Ted Saligari told him how some useless bludgers from Hamilton had shot up their party and earnestly inquired if Donnie had any ideas as to who they might have been. Donnie didn’t. Eventually, when things had quietened down and people could be expected to see the funny side of it, he confessed to Leo that the dreadful deed had been done with Leo’s very own shotgun. Fortunately, the Saligari mob were as much renowned for their sense of humour and practical jokes as for their high spirits, and all was forgiven.

These family narratives are concluded with a few oft-repeated and well-remembered sayings of my parents.

Dad’s.

* Knowingly – “I’m not a fool or the son of a fool.”

* In the same vein – “Anyone who buys me for a fool will lose their money.”

* In confidence – “There’s only two of us in this room …” (or three, or four , or five, etc, however many was relevant).

* Greeting a child (this one of general family usage) – “How’s your belly where the pig bit you?”

* At the table, to Mother – “Good soup, Margaret.”

Mum’s.

* Imparting wisdom – “If you can’t say something good about someone, don’t say anything at all.”

* Comforting – “Vo Vo Vo”.

Dad and Pal Dad and Pal |

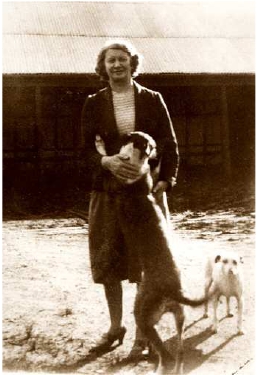

Mum and Snip and Old Nell Mum and Snip and Old Nell |