Keith, about 22 years old, was school-teaching at a little town in the Mallee called Wagant. He was visited there by his younger brother Les, who at the time was fruit- picking in the vicinity. At a local dance Les took a fancy to a good-looking local girl who made it obvious that she had taken a fancy to him, too. This did not at all please the good-looking girl’s boyfriend, who invited Les “out the back” to establish which one was the better man.

The boyfriend was the local heavyweight boxing champion. He was known as The Champion of the Mallee and was probably pretty confident of putting the brash young interloper in his place quick time and with no trouble at all. It so happened, though, that Les had done a bit of pugging himself, was undefeated in boxing troupe bouts and local tournaments and was known as The Champion of the Western District. He had a reputation that extended as far from home as Wagant and to some of the citizens of that township, including its unofficial Mayor, a notable sport and a betting man. That worthy was present the night of the dance. Recognizing a financial opportunity, he prevented the two rivals from leaving the hall and persuaded them of the foolishness of settling their differences in the dark at the back when money could be made from a pre-arranged public stoush with admission fees. And so it was organized that a grudge bout take place in a ring to be erected on the dance floor of the town hall in three weeks time.

Most unfortunately, very soon after the night of the dance, Les began to feel sick from the onset of an illness which would eventually lead to his premature death. He had to quit his fruit-picking job and return home to the Western District. When, inevitably, the word, initiated by the Champion of the Mallee, spread through Wagant that the fight was off not because Les McLeod was sick but because he was scared, the local school teacher was both indignant and mortified. He announced that no McLeod had ever been afraid of anything or anyone and he would take the place of his absent brother, would show the local champion a thing or two and teach him a lesson he wouldn’t forget.

Keith boarded at the home of the Wagant barber, who had been a boxer in his youth and who had a lot of time for his young boarder. So the barber produced his old set of boxing gloves and offered to give Keith the benefit of some training. He very quickly realized that as a boxer Keith was a good school teacher and would be absolutely no match for the Champion of the Mallee.

The barber recognized a desperate situation when he saw one and knew that something must be done to avoid a potential homicide on the dance floor of the Wagant hall. Fortunately, he was by nature an inventive man. From the day of that enlightening spar onwards, customers at the barber’s shop were regaled with tales of how the barber had had the gloves on with Keith McLeod, that Keith was bigger and faster than his brother Les, and that it just wasn’t fair that their local hero, the Champion of the Mallee, should have to face up to a ring-in. It wasn’t long before these tall stories reached the ears of the local champion and gave him cause for cogitation and concern. A man of action, he immediately sought out the Mayor and advised him that his quarrel was with Les McLeod, not with Keith McLeod. He liked Keith McLeod and in the absence of Les McLeod the fight was off.

Thus was pugilistic mayhem averted and the honour of the Clan maintained.

|

|

The Story of Big Les

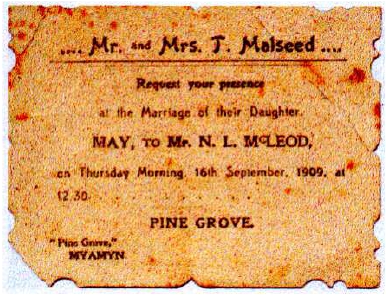

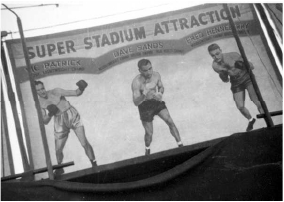

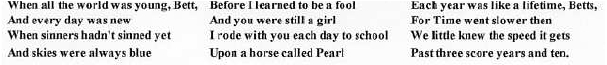

The first Leslie McLeod was later called Big Les within his family to distinguish him from that dear good boy, Little Les, who was born ten months after Big Les had died. The first Les McLeod was a man of varied aptitudes; a renowned breaker of horses in the best horse-whispering tradition, a boxer and a poet. Like his Uncle Rod McLeod, Les had bouts with fighters in boxing troupes of the kind pictured below, and won them all.

As a teenager, Les went back to the Condah school and warned a sadistic schoolteacher of the grave consequences that would follow one more thrashing of younger brother Donnie. (At the Back to Condah about thirty years later, that same sadistic schoolteacher approached brother Donnie with outstretched hand saying “Donnie McLeod! I remember you!” Said brother Donald, white faced with a sudden rage and ignoring the proffered hand, “I remember you, too. You used to thrash hell out of me. Would you like to step around the back and see how you go now?” That ex-schoolteacher was not sighted again, at the Back to Condah or anywhere else.)

At “Westerlea” with Snip and Snap

Les died of tuberculosis, that dreaded disease also called “consumption” and which in an earlier century was known as “The White Plague”. Before the advent of penicillin the only cures for it were fresh air and sunshine, and they very seldom worked. The very low prospects of any cure inevitably gave to the illness a kind of fearful repugnance. Cousin Kevin has told me that he had heard that Les was buried in a coffin sealed with lead.

Though precautions were taken, the general community paranoia could not have been shared at Westerlea. Les spent much of the time of his illness in a glassed-in room on the front verandah, getting the recommended dosages of fresh air and sunshine. I can remember feeling very privileged on an occasion when he and I watched together, from his glass sleepout, an impromptu game of cricket played on the front lawn by other brothers and sisters.

I recall, too, another occurrence which would have taken place after his admission to the TB Sanitarium at Bundoora, just out of Melbourne. Crawling under his recently vacated bed I found a little ball of fluffy house dust and emerged triumphantly with it pinched between my fingers, calling “Mum! Mum! I’ve found the germ!”. Taking it from me, her sad response was that she wished it could be got rid of so easily.

I was only four at the time and did not know that my mother and father went to Melbourne to be with Les when he died. I heard later that they travelled home in the train with his coffin in the luggage van. I remember well the afternoon at Westerlea when I observed from an adjoining room the strange sight of many straight-backed people with straight faces sitting on straight-backed chairs in the sitting room. “What are all those people doing here?” I asked Tom, my eight year old brother. He whispered back “Les is dead.” Whereupon I started a raucous and unseemly wailing that brought my mother rushing to me. “Tis not true that Les is dead, is it?” I sobbed. “No” said Sarah May, hugging me, “He is not dead – he has just gone away”. She was right.

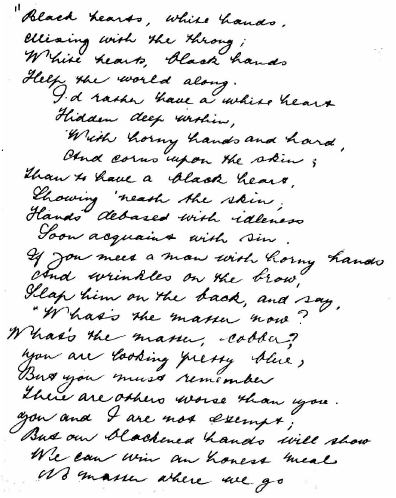

Big Les had several poems published in The Bulletin, a national journal of the time. He often corresponded with Mary Gilmore, later Dame Mary Gilmore, the celebrated poet and activist. After his death, aged just twenty-three, his mother received a letter in which Ms Gilmore deplored the loss of one of the most promising of young Australian poets.

My parents had in their bedroom at The Bunyip hotel a poem by Big Les that I guess was their favourite. The presentation of the poem in its wooden frame included a black and white drawing of a young stockman on his horse.

Leila Lou

| I’ll be glad when Leila’s back Singing down the track again On her little chestnut hack Jogging down the grassy lane! |

Leila with the golden hair – Say, when’s Leila coming back With her ambling chestnut mare Pacing down the grassy track? |

|

| What’s become of Leila, Jack, Little, laughing Leila Lou Leaving all the songs she sang Lingering in the heart of you? |

Won’t come back! O, never dead – Little laughing Leila Lou Leaving all the things she said Sighing in the heart of you. |

|

Maybe the next one is my favourite.

|

His Fiancee, Elsie Vickermann |

Think this of me when sunsets glow Across the hills afar – That I will come when lights are low No matter where you are. Then you will be the bride, my dear And I will be the groom Then you will never cry, dear Alone within the room. The leaves will soon be blown, dear That were so green last Spring But we must live alone, dear And hear the birds sing. Till blossom decks the bough, dear, Until we meet anon Oh, we must live as now, dear till yellow leaves are gone. |

Westerlea

The stories told earlier in this section took place when the family lived near Condah on a farm called Westerlea. I was only five and a half years old when we left the farm and cannot remember a great deal about it. I do recall starting school at the one-teacher school in Condah and I remember the sadistic schoolmaster mentioned in The Story of Big Les. Brother Tom had warned me that if I was ever to get “the cuts” I was not cry. So, one morning when the entire male section of the First Grade, about five or six of us, had for some forgotten reason incurred the displeasure of the teacher and were lined up on the platform to receive a single cut each, I remembered the injunction from my big brother and succeeded in holding back the tears, for which misplaced minor heroics I was singled out to receive six of the best. My prideful pigheadedness was such that even after those I still refused to cry. At playtime my hands were swollen and sore, but Tom said he was proud of me.

Because my memories of Westerlea are hazy, this section is mainly a display of a few old photographs.

|

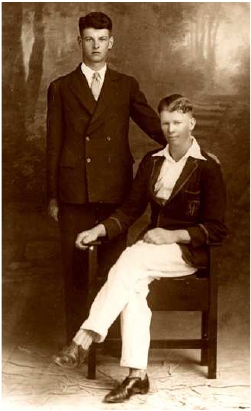

Big Les when Young |

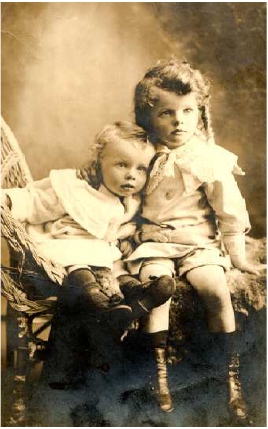

Norma, Aged Four |

Betty, Mum and Alan |

|

Norma, about nine, proudly holding Betty |

Alan and Donnie under the peach tree at “Westerlea” |

|||

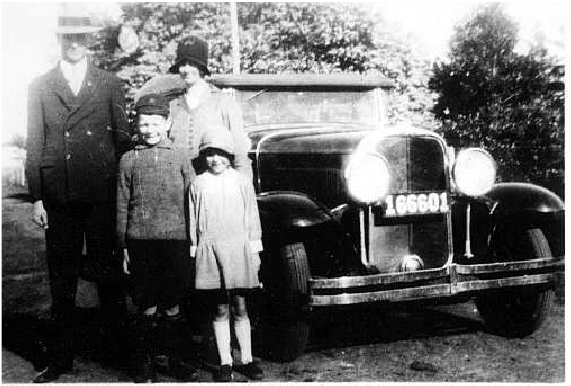

Keith, Alan, Mum, Betty and the Family Car

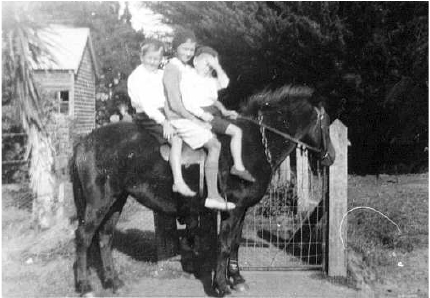

Tom, Betty and I rode the couple of miles to school each day

Before leaving Condah and Westerlea, it is interesting to note how pieces of the original Bassetts Station, some few miles west of Condah, have been part of the lives of various ancestors and their descendants. The original Bassetts was eventually split up into the pastoral runs of Crawford, Kangaroo and Bassetts. Norman and Susan McLeod worked at Kangaroo and at least two of their children were born there. Bessie Murchison worked at Kangaroo before her marriage to Ruairidh McLeod. Her Grandfather Neil and Uncle Donald Murchison both worked at Crawford. Donald Stewart, the brother of Susan McLeod, also worked at Crawford. So did Big Les and Donnie McLeod. And for any years Paul Saligari “laboured in the vineyard” there.