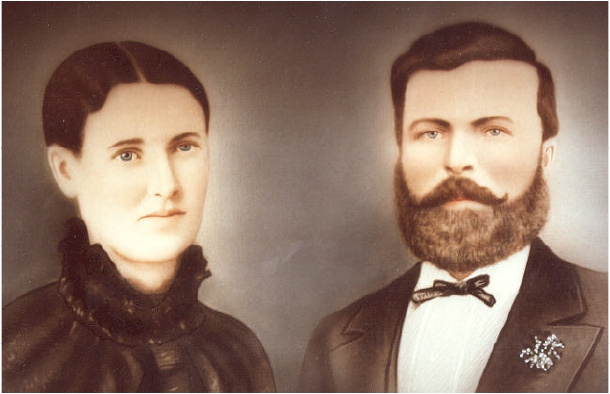

| Husband: | Ruairidh McLeod | |||

| Born: | Abt. 1846 in Parish of Portree, Inverness-shire, Scotland | |||

| Married: | 2 January 1884 in Free Presbyterian Church, Hamilton, Vic | |||

| Died: | 10 September 1936 in Condah, Vic | |||

| Wife: | Elizabeth Murchison | |||

| Born: | Abt. 1859 in Ballarat, Vic | |||

| Died: | 9 May 1935 in Condah, Vic |

| 1 | Name: | Mary Ann McLeod | ||

| Born: | 1884 in Condah, Vic | |||

| Died: | 7 December 1900 in Condah, Vic | |||

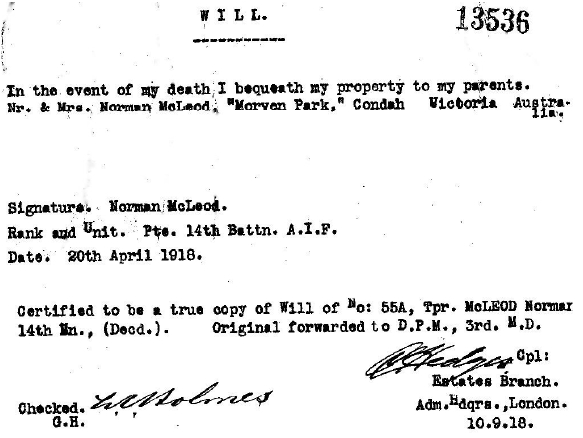

| 2 | Name: | Norman McLeod | ||

| Born: | 9 May 1886 in Condah, Vic | |||

| Died: | 28 April 1962 in Hamilton, Vic | |||

| Married: | 16 September 1909 in “Pine Grove”, Myamyn, Vic | |||

| Spouse: | Sarah May Malseed | |||

| 3 | Name: | Susan McLeod | ||

| Born: | 1888 in Condah, Vic | |||

| Died: | 3 September 1975 in MacArthur, Vic | |||

| Married: | 1914 in Vic | |||

| Spouse: | David Albert Annett | |||

| 4 | Name: | Donald McLeod | ||

| Born: | 1890 in Condah, Vic | |||

| Died: | 1956 in Hamilton, Vic | |||

| Married: | 1926 | |||

| Spouse: | Bessie Ruth Dougheney | |||

| 5 | Name: | Marion McLeod | ||

| Born: | 26 October 1893 in Condah, Vic | |||

| Died: | 10 January 1969 | |||

| Married: | 1927 | |||

| Spouse: | Roy Price | |||

| 6 | Name: | Malcolm McLeod | ||

| Born: | 26 October 1895 in Condah, Vic | |||

| Died: | 31 March 1975 | |||

| Married: | 1929 | |||

| Spouse: | Elizabeth Monica MacDougall | |||

| 7 | Name: | Roderick Charles McLeod | ||

| Born: | 5 December 1898 in Condah, Vic | |||

| Died: | 15 January 1967 in Condah, Vic | |||

| Married: | 15 September 1933 in Presbyterian Church, Hamilton, Vic | |||

| Spouse: | Irene May Kelly | |||

| 8 | Name: | Charles Leslie McLeod | ||

| Born: | 1902 in Condah, Vic | |||

| Died: | 1978 in Pakenham, Vic | |||

| Married: | 1929 | |||

| Spouse: | Margaret Olive Ester Wallace | |||

Ruairidh and Bessie’s first home was on a hill in what is now the Elgin property. That hill is still known as McLeod’s Hill, and their old property Albanella is on McLeod’s Road, not far from the small town of Condah. Albanella, incidentally, is Gaelic for Other Scotland. My older brothers have told me of how Ruairidh and Bessie would speak to each other in the Gaelic when they wanted to say something that was not suitable for the ears of visiting grandchildren.

Although Bessie was born in Australia, Gaelic was the language spoken at home by her parents, Malcolm Murchison and Mary McKenzie. Bessie was born in about 1859, some five years after their arrival in Australia from the Isle of Skye. It’s “about 1859” because Bessie’s birth was not registered. Her marriage certificate states that she was born in Grenville, Victoria; her death certificate says she was born in Ballarat (which was in the County of Grenville). It seems very likely that at the time of her birth Malcolm and Mary had forgotten they were lazy Highlanders and were still engaged in an arduous search for gold. Certainly, Malcolm’s occupation in June 1855 is shown on the birth certificate of his firstborn, Donald, as Gold Digger.

Their marriage certificate gives Ruairidh’s place of residence as Condah, Parish of Normanby, and Bessie’s as Kangaroo, Parish of Normanby. It seems likely that before her wedding Bessie was a live-in employee at Kangaroo.

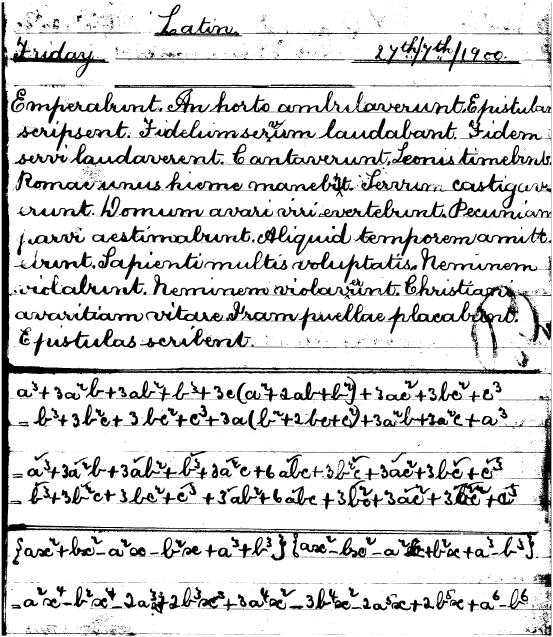

Their first-born, Mary Ann, died at the turn of the century when she was sixteen years old. She had still been attending school the year she died and, judging by a schoolbook of hers that survives to this day, she was an outstanding student.

A Page from Mary Ann’s Schoolbook

A Page from Mary Ann’s Schoolbook

Bessie’s brother Charles Murchison, who was born in Ballarat in 1856, married Frances Orsburne. They moved to Corowa in NSW and Frances died there in 1902 (two years after the untimely death of Bessie’s Mary Ann) leaving a three year old daughter named Mary. Ruairidh and Bessie brought Mary Murchison up like one of their own. She fitted in between the two youngest of their children: about one year younger than Rod and three years older than Charlie. At twenty-one Mary married George Hollis.

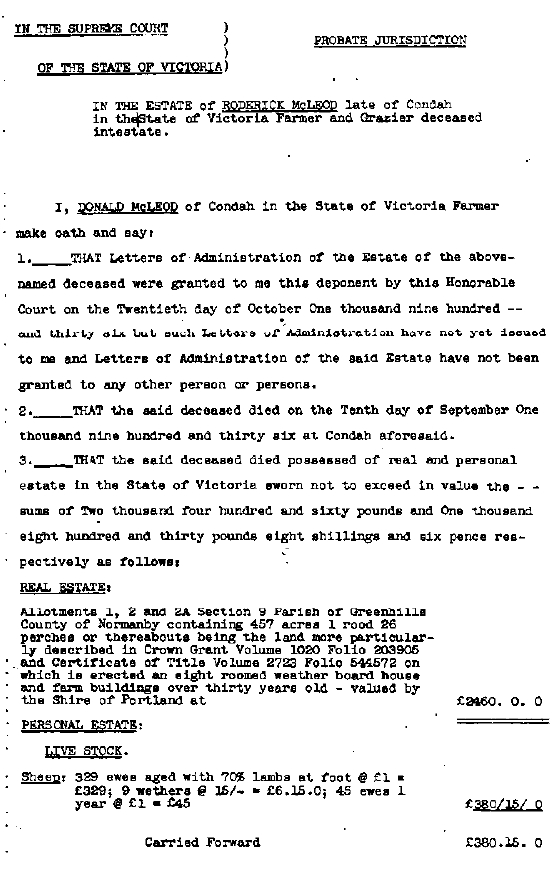

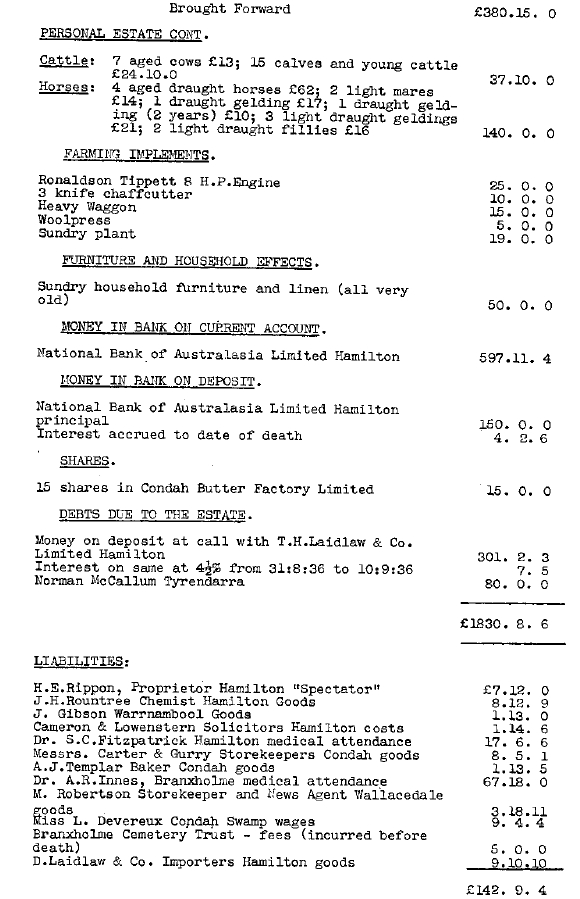

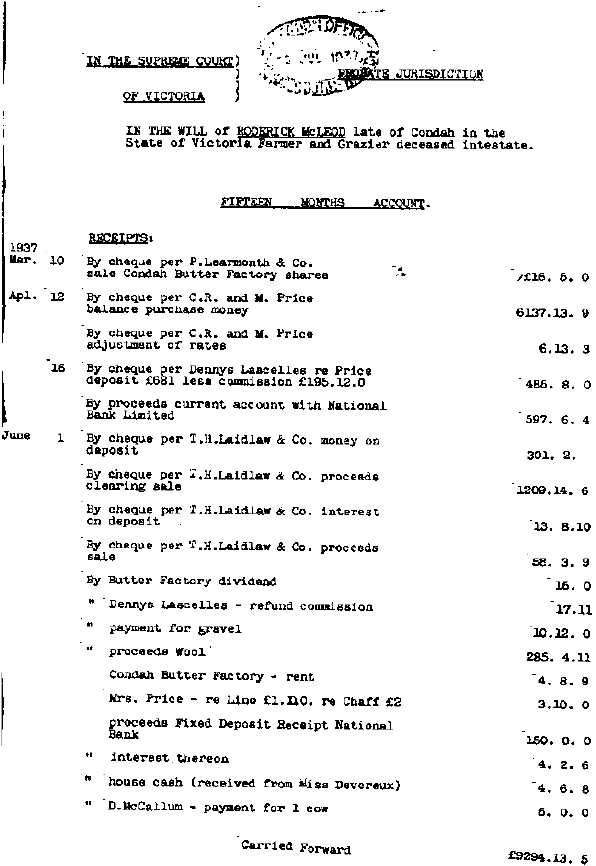

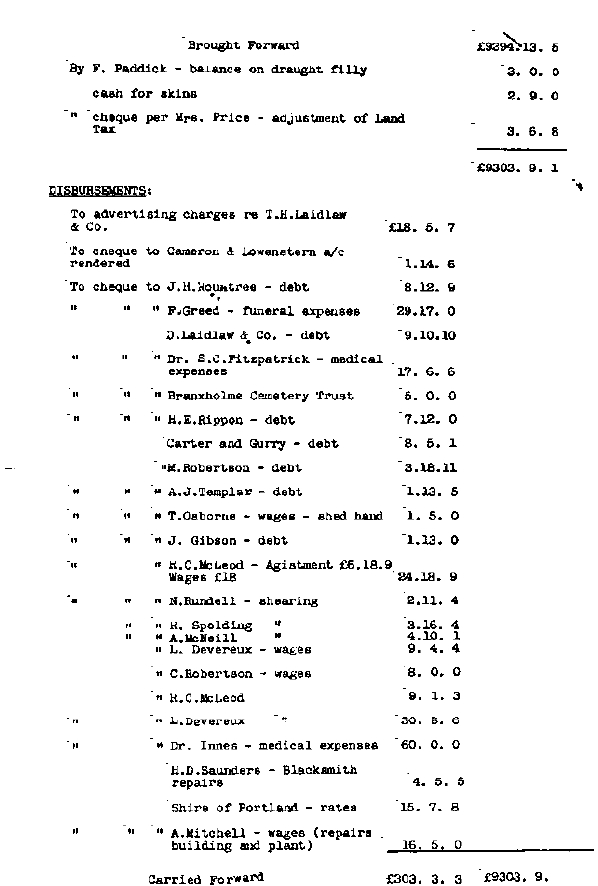

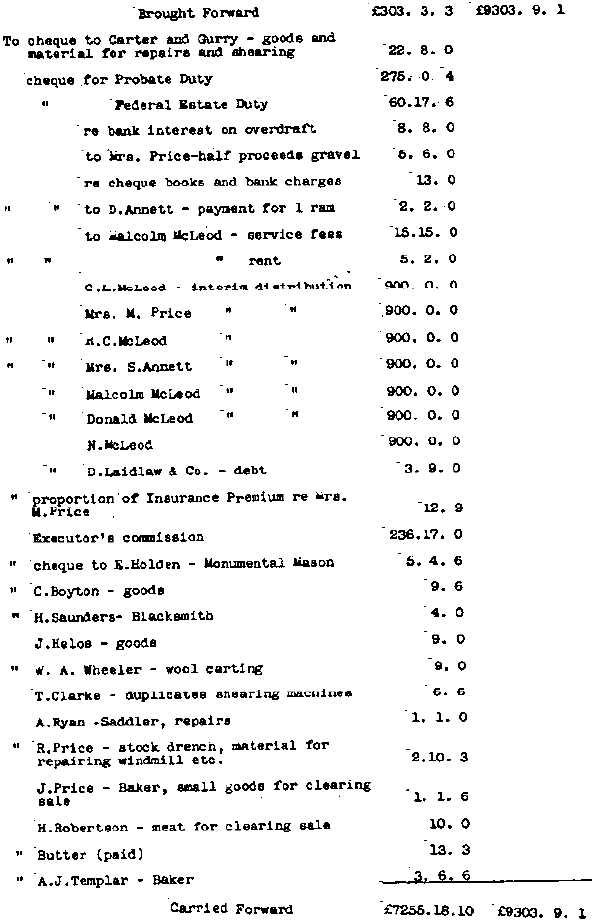

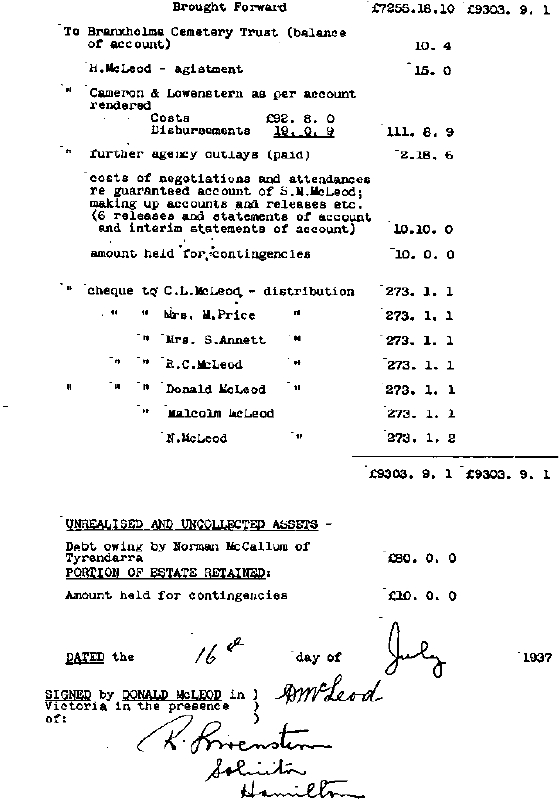

Ruairidh must have worked hard and long, and bought and sold cannily, because in his lifetime he accumulated assets of considerable worth, as evidenced by the following copies of some pages of his probate papers selected for their general interest.

The real estate of 457 odd acres referred to on page 42 does not tell the full story of Ruairidh’s material worth. He may never have gone to school, but he must have known a thing or two about probate, death duties and tax minimisation. The fact that he died without having made a will meant that his estate was divided equally among his surviving children. My brother Alan has told me that before his death in 1936 Ruairidh had already split the bulk of his land up between his sons − cousin Kevin says that the sons drew straws to decide who would get which blocks. Apparently part of the deal was that the sons would raise the money necessary to enable the two daughters, Susan and Marion, to receive equivalent shares in cash; and this they did.

My father Norman got the block called the Cherrytree; brother Alan informs me that our father had to mortgage it to find his share of the cash that went to Susan and Marion. I have seen a copy of the notice of a public auction at which, on 17 August 1911, Ruairidh purchased the Cherrytree. The property consisted of 893 acres 1 rood and 37 perches and had been previously owned by the Hon. S. Winter Cooke. Kevin has told me that the Cherrytree was the largest of the blocks given by Ruairidh to his sons, some of whom received significantly smaller acreages. My conservative estimate of the overall average size of the gifted blocks would be 500 acres. That’s roughly the size of the land that Ruairidh retained, which was valued on page 42 at £2,460. Multiplying £2,460 by the number of his sons (5) gives £12,300 pounds worth of land distributed by Ruairidh before his death. To look at it another way, the acreage held by Ruairidh before the distribution would have roughly totalled 500 x 6, or 3,000 acres. That’s a fairly large lot of land, and a considerable advance on the 158 acres that his father Norman had before he died.

That’s more than enough on materialistic matters.

One fine Sunday morning Ruairidh McLeod, as was his wont, was on his way to church; on this occasion accompanied only by his son Donald. Donald, the future administrator of his estate, was then about eight years old, so Ruairidh would have been about fifty-two. They were travelling along nicely in the gig when they came upon a man mounted on a horse travelling in the opposite direction. We’ll call this man Dogsbody. Ruairidh pulled his horse to a halt and surveyed the mounted man, who had also halted.

“That’s a fine looking horse you’ve got there, Dogsbody,” says Ruairidh. “It’s a pity you haven’t paid for him.”

This doesn’t sound like a very friendly Sabbath greeting, and it wasn’t. Dogsbody had acquired the horse from Ruairidh about three months earlier. He had pleaded temporary hard times for not being able to make any immediate payment but had promised to pay in full within a month. He hadn’t been seen since.

Dogsbody was recalcitrant. His response was “I won’t be bullyragged by you, McLeod.” At which Ruairidh rose to his feet on the floor of the gig, saying “Bullyrag or no bullyrag, there’s nae principle in ye. Haud the reins, Domhnall.” Young Donald grabbed the reins as Ruairidh launched himself from the gig, tackling Dogsbody amidships and knocking him out of his saddle to the ground. Dogsbody got to his feet second and Ruairidh promptly knocked him to the ground again. This time he stayed there.

Ruairidh seized the bridle of the riderless horse, tied it to the back of his gig and proceeded on his way to church, leaving Dogsbody sprawled in the dust of a country road. After worship the horse went back home with its bridle, its saddle and its rightful and righteous owner.

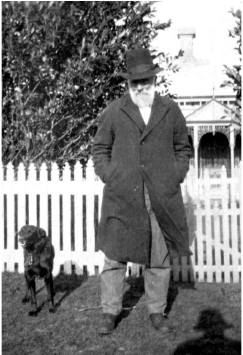

The picture of Ruairidh mounted on his black horse Vanity and followed by his dog Glen was taken many years after that Sunday morn on which the “Bullyrag” episode occurred.

My childhood recollections of my grandparents are very scanty and vague. I remember Ruairidh’s white beard and the aura of authority that surrounded him and earned the utmost respect from small grandchildren and, I suspect, larger others. About my grandmother I remember her white bunned hair, her bright blue eyes and her warm and loving hugs.

The Bullyrag story was one of my father’s favourites. He was almost invariably overcome by mirth before he got to the end of it. I think that I heard all of it on only one occasion. He must have decided then that the full story should be preserved for future generations.

A very small aside about my father Norman, the teller of tales, would seem to be in order here. Like most of his Scottish contemporaries he had no second name; to distinguish himself from the other Normans in the extended family he adopted the styling Norman L McLeod. The letter L signified nothing more than the convenience with which an L could be added to an N to effect a proprietory brand for sheep and cattle, like this:

![]()

Two Condah families had for many years been in a state of feud. Although neighbours, their resentment of wrongs done in a past so distant that no one could remember exactly what those wrongs were, was such that they never spoke to or in any way acknowledged one another.

One Saturday night there was yet another Farewell at the Condah Hall to say “good bye” and wish “good luck” to a young local resident on his way to the horrors of the First World War. Almost everybody in the district attended, including the two feuding families. A long row of conveyances, with their horses still between the shafts, were tied up as usual to the post and wire fence that enclosed the hall. The buggy of one of those feuding neighbours was drawn by a black horse and that of the other by a white horse.

The White Horse The White Horse |

and the Black Horse. and the Black Horse. |

Not everyone was inside the hall during the proceedings. Rod and Charlie McLeod were outside, in their teens, up to mischief. The first prank they got up to was to move the black horse with its buggy from its place in the row and place it beside the white horse. The next was to unharness both horses, lead them through a gate to the other side of the hall fence, push the two buggies forward so that the shafts extended through the fence into the hall paddock and re-harness the horses, but each to the wrong buggy. The horses were now on one side of the fence, harnessed to incorrect buggies on the other side. You’d think they’d have been satisfied with the potential turmoil thus created but their inventiveness was not ended; worse was to come. With the aid of a bucket of whitewash and a bucket of blacking they turned the black horse into a white horse and the white horse into a black horse. By this time the hall function was nearly over and the two miscreants repaired to a vantage spot to witness the results of their misdeeds.

It took quite some time in the dark for the owner of the black horse to find the new location of his buggy. When he did, it was to find his longtime enemy cursing and swearing at the discovery that the reason his buggy wasn’t going anywhere was because there was a fence between it and ‘his’ horse. The other thought that uproariously funny until he discovered that he was in the same predicament. Together they unharnessed the horses and got them on the same side of the fence as the buggies. In the excitement and the dark they didn’t realize that their horses had been switched. They had, however, for the first time in years, exchanged words with each other. They were colourful words describing the scoundrels who had done this vile deed and the fate that awaited them when they were found out. Finally the two horses were reharnessed and a minor miracle occurred. As the two warring families drove away, they called out “Goodnight” to each other.

It was not until the following morning, after some early rain had washed off much of the whitewash and the blacking, that the discovery was made that each had the other’s horse. Each immediately proceeded to return the horse that wasn’t his. When they met halfway, handshakes were exchanged as well as horses. So ended one of the district’s longest-standing feuds. Rod and Charlie were well pleased with the night’s activities.

The preceding stories were told many times and always with great gusto by my father. Any embellishments are not mine.

Ruairidh and his dog Glen Ruairidh and his dog Glen |

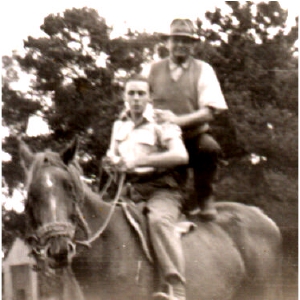

Robin, Rod and Scotty Robin, Rod and Scotty |

The story goes that when Glen was young Ruairidh sold him to a passing drover. Glen got away from his droving master at Little River near Geelong and returned, faithful but footsore, to Albanella. Ruairidh never sold him again.

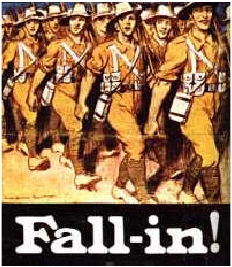

Donald McLeod enlisted in the 1st A.I.F. on 17 July 1915. Here, for its historical value and interest, is a copy of his Oath of Attestation. It looks as though the date thereon had at the time for some reason been changed from 21st inst to 26/7/15.

Uncle Donnie’s service record shows that he embarked for overseas duty on 11 October 1915 and on 26 February 1916 was transferred from the 8th to the 6th Battalion. On 30 March 1916 he arrived in Marseilles from Alexandria, and was sent to The Somme. As the book of that name by John Laffin has it: in 1916 the Somme was a killing field. Many of its place names have become famous and infamous in Australian military history: famous for heroic endeavour and stubborn fortitude, infamous for slaughter, suffering and inept leadership. A transcript from the Hamilton Spectator of 23 November 1916 follows.

WITH THE AUSTRALIANS IN FRANCE.

Writing to his brother, Mr Malcolm McLeod, of Albanella, Condah, under date France, August 8, Pte D. McLeod says :–

I suppose you have read in the papers ere this of the great charge and good work done by the —- division at —. The — and —- brigade went in first, and cleared the Germans out of a couple of lines of trenches. They charged in the early hours of the morning. Of course, our artillery had bombarded the German lines for hours beforehand. We were in supports the night they attacked, and marched up close to where the battle had been in the early hours of Sunday morning. Oh, I shall never forget that sight as we went along that shell-torn road, but it was nothing to what we saw and went through afterwards.

On enquiring from the wounded how things were going in the firing line, some one replied “Things are hot up there mate.” One chap said, “It is a perfect hell up there.” Our company halted in a trench, where they were fairly safe. They were to be kept there as a reserve for the time being. We were not there long when about a quarter of us were ordered to carry supplies, ammunition, etc. up to the first line. We had to go along the road that the Germans had held the night before, and over the ground where the battle had been fought.

Jack McGrath said, “You and I will carry together.” Poor fellow, he was killed two days later. We had been together ever since we went into camp and were on outpost together in the desert at Serapeum Egypt, and here in France we were in the same company and on the same watch log the first time we went into the trenches. He was as cool and game as you could get. We hadn’t gone far when we met about 50 German prisoners taken by our boys in the fighting. A little further on we went over a bit of a rise. It was littered with wreckage of every description, broken carts, wagons, etc., rifles, ammunition, and bombs lay everywhere, as they were dropped by the dead and wounded.

The road was full of shell holes, as the Germans shelled it for all they were worth, for they knew that we would have to bring supplies and reserves along it. All along that road shells were falling, men were getting wounded and killed as we went along. However, Jack and I got to the first line safely. I shall never forget that sight. It is impossible for me to describe or you imagine. It had been a wood, but not a limb or leaf was left by our bombardment. Big trees had been shattered and uprooted. The trenches the Germans had held the night before were blown about terribly. Of course their dugouts were pretty good. It is almost impossible to hurt them, but I will say more about them later on. I don’t think there was a foot of ground that had not been blown about by shells. Some of the shell craters were that deep and big that you could back a horse and cart into them. Perhaps you remember the pictures of San Francisco after the earthquake and fire. It reminded me something of that scene. Only there were dead lying about everywhere. At the entrance of the dugout I saw six dead Germans piled on top of one another.

The German dugouts are marvellous. Some of them are 50 ft. deep under the ground, and when you go down them it is like going down a ship. Some of them are fitted up very elaborately, even have carpets on the floor, and were lit with electric light. They also had heat. They evidently thought they were never going to be driven back. When our artillery would bombard they would go down the dugouts and be quite safe. Our only chance was to get across as soon as our artillery fire lifted and catch them before they had time to come up out of the dugouts. Then it was an easy matter to bomb them out.

Jack McGrath said, well I never thought we would get back, Don. No doubt it was hot. For two days we were carrying stuff up to the firing line. Next morning early we went in to do our part. But didn’t know what it was. As we passed through one trench we were halted and told to leave our overcoats there. (We hadn’t carried pack or blankets in, only overcoat and waterproof rolled up.) We were then told we had to make a new firing line, that we had to advance out into no man’s land past our own first line. Remember this was not at night time, but in the middle of the day. Our platoon commander told us we would be under all sorts of fire all the time we were digging in, but never mind how we were shelled, or how many were hit we had to keep digging. Jack McGrath was near me as we rolled our coats up, and said, “I suppose we may as well roll them up properly, but a lot of us will never need them again.”

We doubled out over our own first line to where we were to dig in, and started to dig for our lives. I didn’t think we would last ten minutes. In the first twenty minutes three of our sergeants were hit. We only had four, also our two master sergeants and two officers out of four, all within the first half hour. They couldn’t carry away the wounded and men had to be taken out of the trenches to put on stretcher bearing. We got dug in by dark, but those who were not on watch kept on working and improving the trench. No one was allowed to sleep, and they couldn’t have slept even if they were allowed, for the Germans shelled us continually, and a good few men were hit during the night. Our steel helmets saved many a life. My helmet was hit often with shrapnel. During the night I was blown off the firing step by the explosion of a shell, almost on our parapet, but was not hit.

Next day we further improved our trenches, and we had just finished our bay, and were going to sit down on the floor of the trench for a rest, when I noticed that my bayonet had been broken by shrapnel, so I worked my way a bit along the trench to see if I could get a spare one. I had got along about half a chain, and was talking to Argyle and a couple more, when I heard a fall of earth and cried for help. Something told me they came from my bay. I rushed back and snatched a shovel from a chap as I passed. The bay had been knocked in by a shell, and every man in the bay was buried, nine of them, only Geo. Dunn’s head was above ground. The rest were completely buried. Three or four of us dug for all we were worth, but it took a long time to get them out, and the Germans must have seen that they had knocked the trench in. They could also see us working and they shelled us for all they were worth, and also tried to snipe us. We got them all out, and none of them had any bones broken.

Charlie Read was one of the most unselfish fellows I ever met, and there wasn’t a lazy bone in his body. I sent his photo home last Christmas, he and Harold Cuthbertson taken on a log. His father is a widower, and is over 70, and that accounts for Charlie being as handy as a woman. All the others that were buried were sent away suffering shock. Jack McGrath was killed the same day. A man in his bay was badly wounded, and Jack and two more volunteered to carry him back. They had to carry the wounded about a mile and a half under shell fire all the time. They got down all right, but on the way back Jack and another chap named Jennings were killed by a shell. Jack was one of the whitest men I ever met, also the coolest and gamest. Colin Duncan, George Dunn, and H. Davies were all wounded. They also went into camp with Mac and me, and we had been together ever since.

Before we went into the last fight there were eight of us who had been together ever since we went into camp (nearly a year now). There are only three of us left now. Two are dead and three are wounded. Charlie Nesbitt, from Coleraine, was killed while stretcher bearing. Jim Smith was not in with us. Luckily for him, he was on guard with the A.S.C. for a few weeks. He has rejoined us since we came out. Les Power, from Branxholme got through alright. Men who were on Gallipoli from the landing to the evacuation say that Gallipoli was nothing to our last stunt. Men were being sent away with shell shock all day. Our other times in the trenches were play in comparison to this. They say it was as bad as Verdun. The German prisoners say it was worse. A good few prisoners were taken all together. Lieutenant Taylor was also killed. He used to be assistant to the Rev Williams and was stationed at Macarthur. I met him at Cannon’s once.

We have got a lot of reinforcements during the last week to fill the gaps in the ranks. No doubt they will turn out good fellows when we get to know them. But, oh how I miss the dear old boys who have gone. In the ranks when I look to my right or left, I see fresh faces where the old familiar faces used to be. Some of them will have a place in my heart and memory while life lasts, be it long or short.

I must try and write to Charlie Read’s father and Jack McGrath’s mother. She is a widow but has other sons and daughters; also to C Nesbitt’s people, as I don’t think anyone else here came from the Coleraine district. I saw Fred Glare since coming out. Also saw Hughie McLachlan the day after we came out. He was well, but only had time to say a few words as we marched past. He has not been in any fighting in France yet. Also saw Alan McKinnon the same day. I spotted him as we marched past, and sang out to him. He marched along with me till we stopped for a spell and then we had a good yarn. Also Joe Sharrock. They had not been in the firing line then, but suppose they have been ere this. I understood from Allan that Duncan’s wound was caused through a bomb accident.

I thought this would catch to-day’s mail, but couldn’t finish it last night before dark. We did not have our clothes off for three weeks until a couple of nights ago and got our blankets back then. Prior to that we only had our waterproofs and overcoats, and while in the stunt only our waterproofs. We have been sleeping out in the open for the last three weeks.

Pte Donald McLeod

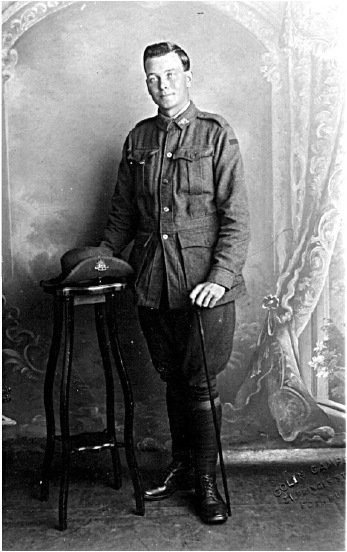

On the back of the above picture is written

“To Auntie Annie, with best love from Donnie, France, 24-9-17”.

I suppose that Uncle Malcolm gave his brother’s letter to the Spec because he reckoned, quite rightly, that it deserved a wider audience than the immediate family. My brother Alan recalls being told of another, less-publicised, letter that Uncle Donnie wrote from the front. It was to his father Ruairidh and its message was “Don’t let Malcolm enlist.”

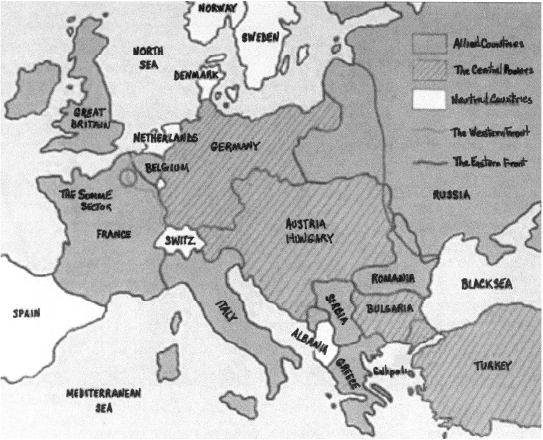

World War I was the greatest conflict the world had ever seen. It was a fight for supremacy between the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary and Turkey) and the Allies (France, Great Britain, Russia, Italy, Japan and, from 1917, the USA). It also involved many countries which were colonies and dependencies of those major powers. In the aftermath of the war Germany and her allies were made to take the blame for starting it by their militarism. But both sides took part in the build-up of arms, the struggle for colonies and markets and the creation of a fragile balance of treaties and alliances, thus implicating everybody in failing to avoid conflict. (From Hobart Mercury of 25 April 2002).

After the Battle

On 5 October 1917 Pte Donald McLeod was wounded in action with what his Casualty Form describes as multiple gunshot wounds to his left eye, arm, thigh and leg. His injuries were so grievous that he was presumed not to be alive and thrown onto a pile of fellow-Diggers awaiting a mass burial. He escaped being buried alive when a stretcher-bearer called out “Hey! That fellow moved!” Uncle Donnie returned to Australia on a Hospital Ship on 5 March 1918. Not all were so lucky.

A WWI Australian Cemetery, France

A report of Donald’s Welcome Home, organized by the Political Labor Council (PLC), was in the Hamilton Spectator of 6 June 1918. (The PLC was a forerunner to the Australian Labor Party and a leading opponent of conscription.) The Spec noted that,

Mr J H Black, the presiding chairman,

Conscription was an issue which had bitterly divided the Australian war-time community. Two conscription referendums put up by Prime Minister Billy Hughes were narrowly defeated. An item in the Hamilton Spectator of 30 July 1917 makes it clear that by that date Uncle Donnie’s views on the issue were no longer shared by his cousin Norman (Scotty) McLeod, the eldest son of Ruairidh’s brother Norman. Scotty, a veteran of the Boer War, had enlisted in the 13th Light Horse Regiment of the A.I.F. on 29 January 1915 and embarked on 4 September 1915. From abroad he wrote to the Spec:

He included the following poem.

To My Cobbers in Regret

| Would you see Australia ruined While you’re staying safe at home, While your mates are fighting bravely In a country ‘cross the foam. |

There are many who are lacking In response to Hughes’ call Yet the mother land is waiting, So get ready one and all. |

|

| Do you read the Roll of Honour That appears from day to day Don’t you see the names of cobbers Will you mock them while you stay? |

Join up now and reinforce us As our ranks are thinned, you know We will welcome you as comrades And forget the fatal No! |

|

| You can little know the hardships That your mates have undergone, These thirty months and over They have kept you from the Hun |

Let you Party feeling wither In the fire within your breast, We are forced to love Australia And in actions lie the test. |

|

| Yes, their losses have been heavy And who’s going to take the place Of the men who have one under To uphold the British race? |

So hurry up and swell our numbers, Help to down old Freedom’s foe, Though the path is hard and tiresome Yet shall our manhood grow. |

|

| Give up your life of pleasure Learn to use and load a gun; Be worthy of your ancestry That victory may be won. |

And Australia shall forever Be as free as wattle bloom, Then the altars of our duty Shall reward our present gloom. |

Scotty McLeod, in 4 Bn Aust C’wlth Horse (Boer War) uniform complete with bandoleer

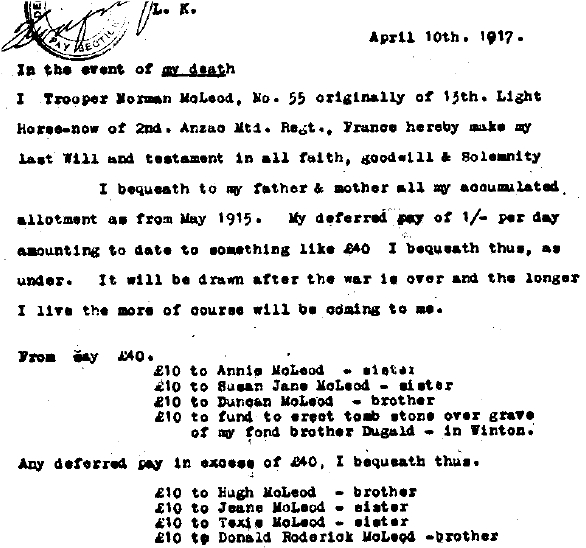

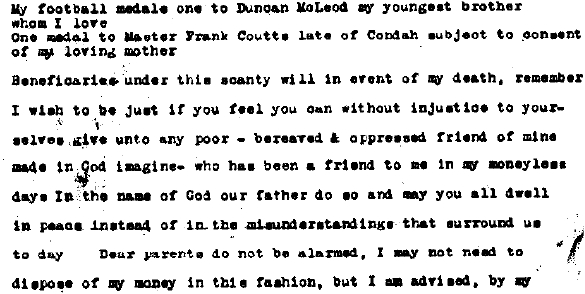

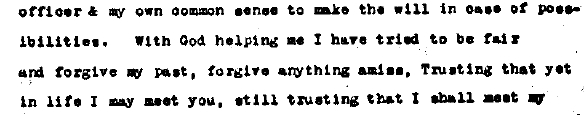

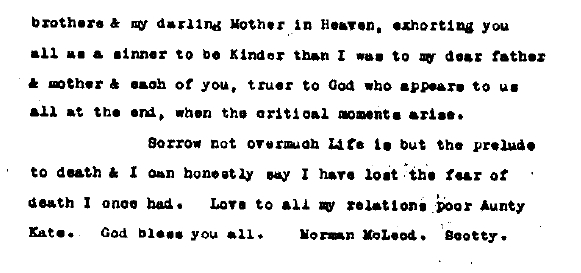

Scotty McLeod was killed in action in France on 31 May 1918. His service record contains two wills, one made on 10 April 1917 and the other on 20 April 1918. Both are copied below, the first for its Gaelic pathos and the last for its contrasting simple directness.

There follows an earlier poem, probably written in the 1890s when Scotty was a teenager. Had its title not been lost we might know the name of the subject of his lament.

| Gone from the friends that loved him, Gone from this world so gay, Gone in his blooming manhood Far, far, away; |

| Gone like the stars that glimmer, Gone like a dried-up stream, * Gone like the winsome pictures Of Youth’s proud happy dream. |

| But in that land of Eden Where bloom no fading flowers, Far from this world of sorrow, Amid the heavenly bowers |

| He kneeleth now and prayeth At the great white throne of God; To Christ our loving Saviour, Who raised the inflicting rod |

| That took from our friends their brother, On that scorching summer’s day. Not one was near to tend him As in the bush he lay; |

| His bullocks they fed near him When our loved one was found; Uncaring of his tragic fate * They chewed their cuds around. * |

| Then to the father’s dwelling The sad, sad news was told, That in a room at Condah His son lay stiff and cold. |

| God help that aged father To bear the chastening rod; God help the poor young brother And sisters that he loved. |

| The New Year’s sun dawned promising Within that old man’s home, But ere it set the fourth time His joy and pride was gone. |

| Gone like the Smoky River That runs before his door– In winter it is flooded But in summer it runs no more. |

At ‘Albanella’ about 1920 – Ruairidh, Bessie, Charlie, Marion, Rod, Donald and, holding the horse, Malcolm At ‘Albanella’ about 1920 – Ruairidh, Bessie, Charlie, Marion, Rod, Donald and, holding the horse, Malcolm |

||

About 1923 – Linda Annett, Uncle Dave, Malcolm, Aunty Susy and Violet About 1923 – Linda Annett, Uncle Dave, Malcolm, Aunty Susy and Violet |

||

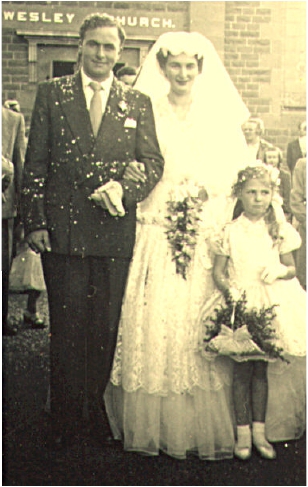

1909 – Norman McLeod and Sarah May Malseed 1909 – Norman McLeod and Sarah May Malseed |

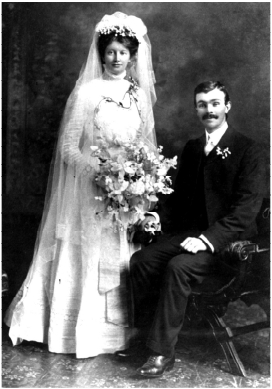

1914 – Susan McLeod and David Albert Annett 1914 – Susan McLeod and David Albert Annett |

|

1926 – Donald McLeod and Ruth Dougheney 1926 – Donald McLeod and Ruth Dougheney |

1929 – Malcolm McLeod and Mona MacDougall 1929 – Malcolm McLeod and Mona MacDougall |

|

Uncle Rod, Uncle Roy Price, Maurice, Kevin, Peter the Italian POW and Uncle Malcolm, all carting in at Rod’s in 1944 Uncle Rod, Uncle Roy Price, Maurice, Kevin, Peter the Italian POW and Uncle Malcolm, all carting in at Rod’s in 1944 |

||

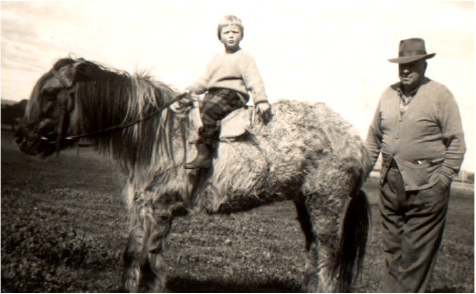

Kevin and his Uncle Malcolm the Equestrian Kevin and his Uncle Malcolm the Equestrian |

1954 – Wallace McLeod breaking-in 1954 – Wallace McLeod breaking-in |

|

1951 – Marion Holcombe nee McLeod at ‘Lochiel’ 1951 – Marion Holcombe nee McLeod at ‘Lochiel’ |

John McLeod at Elm Park about 1953 John McLeod at Elm Park about 1953 |

|

Rod and Rene at the Debutantes Ball Rod and Rene at the Debutantes Ball |

||

Kevin and Lesley MacLeod – Wedding Day Kevin and Lesley MacLeod – Wedding Day |

Kevin MacLeod’s wife Lesley, his daughters Fiona and Deirdre and Aunt Marion Kevin MacLeod’s wife Lesley, his daughters Fiona and Deirdre and Aunt Marion |

|

Deirdre and Rod with Mickey Deirdre and Rod with Mickey |

||

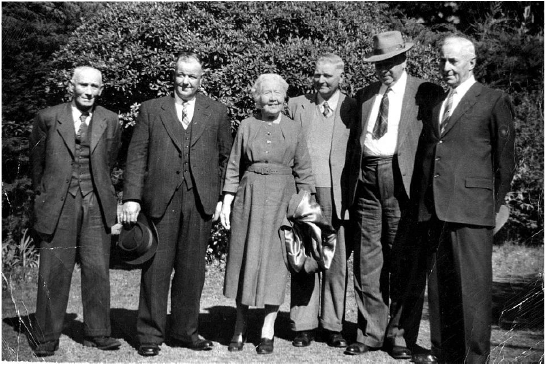

Hughie Mcleod, Charlie, Dame Flora (Chief of The Clan), Malcolm, Rod and Dave Annett Hughie Mcleod, Charlie, Dame Flora (Chief of The Clan), Malcolm, Rod and Dave Annett |

||

Rod McLeod Rod McLeod |

Norman Mcleod Norman Mcleod |

|