Our McLeod ancestors, Norman and Susan, came to the Western District of Victoria from the Isle of Raasay, where they had lived in the hamlet of Balmeanach near Raasay’s western shore. The Isle of Skye is only a mile or so away, its majestic mountains clearly visible across the narrow separating strait of ocean called the Sound of Raasay. The Parish of Portree, administered from the town of that name on Skye, included Raasay.

In 1854 when they left Raasay Norman was about 35 years old and Susan 31. They took with them their children Ruairidh (8), Norman (6), Lexy (4) and Mary Ann (an infant). They were accompanied by 126 other Raasay people who were leaving their island home forever to travel to a far-away land and an unknown future. They were all part of a great exodus from northern Scotland known as The Highland Clearances.

They had not freely chosen to leave their native home or the clanspeople that they left behind. They had no real alternative: they were no longer required. Eleven years earlier, being unable to settle his gambling debts, John McLeod, twelfth Chief of Raasay, was made bankrupt and the Isle of Raasay was bought at auction for 35,000 guineas by one George Rainey. For centuries the inhabitants of Raasay had been mainly farmers and fishermen without sufficient means to pay more than a token rent to the laird of the land, McLeod of Raasay. Their main value to him was not the relatively meagre amount of money they brought in but the fact that the able-bodied men amongst them constituted his standing army, ready and willing at any time to take up their claymores and fight any foe he nominated. After the Battle of Culloden in 1746 the bearing of arms by Highlanders (other than those in a British army) was made illegal by the Government in Westminster. This act had the intended effect of changing the relationship between the clansmen and their Chiefs.

In the new social climate proprietors of Highland acreages could make much more money from a property occupied by sheep than one populated by subsistence farmers. Steps were therefore taken to make life very difficult for the Highland crofters and to “encourage” them to emigrate. Owners progressively moved tenants to smaller and stonier pieces of land, at the same time increasing the rents to be paid. People unable to pay the rent were simply evicted. If they refused to go their homes were burned over their heads. These policies were actively supported by the government in London, which city had too many times in the past been imperilled by invading armies of kilted Highland ‘savages’.

It is an over-simplification to put the entire blame for the Clearances on the introduction of sheep farms. There were other related reasons. One was an earlier change to the method of land tenure enforced on the Highlands by the brutish government, again with the aim of breaking up clannish bonds. The prior Highland runrig system was a communal one whereby land for farming was allotted by tacksmen to a group of clanspeople rather than to individuals. The change to contracts specifying plots and persons facilitated the movement of crofters to ever smaller plots of ground. The Highlanders, like their Irish cousins, learned by necessity that potatoes provided more nourishment per square yard than did the traditional crops of oats and barley. From 1846, however, the Highlands and Islands were plagued by the same potato blight that commenced its devastation of Ireland in 1845.

In 1852 the Highland and Island Emigration Society (HIES) was formed in London to facilitate the dispatch of Highlanders to a new land, and Australia was chosen as the destination. The discovery of gold in 1849 had caused a great number of Australian workers to quit their employment and join in the Gold Rush. In particular, an acute shortage of agricultural labour resulted. At the same time there were in Scotland thousands of redundant and starving agricultural workers. (On Raasay, as elsewhere in the Highlands, severe malnutrition had become commonplace.) Sending the Scots to Australia was claimed to be a solution to the problems of both countries. The May 1990 edition of the magazine Scots Link reported that it was said of the Highlanders at the time: They are familiar with the care of sheep, and family ties cause them to emigrate in masses; while their indolent temper and dislike for long-sustained labour would make the pastoral life of Australia entirely suited to their taste, and discourage them from an arduous search for gold. That little burst of bigotry surely typifies the attitude of the dispossessors to the dispossessed.

Blackfaced Usurper Blackfaced Usurper |

Skye in Background, Usurping Sheep in Foreground Skye in Background, Usurping Sheep in Foreground |

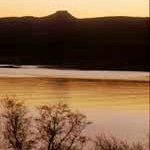

Dun Caan at Dawn Dun Caan at Dawn |

The Ruins of Norman & Susan’s Raasay Home The Ruins of Norman & Susan’s Raasay Home |

Raasay House – Home of the Chiefs Raasay House – Home of the Chiefs |

|

Looking across the Sound of Raasay Looking across the Sound of Raasay |

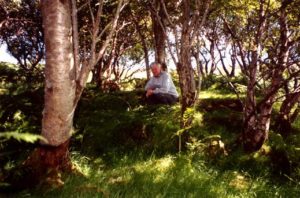

A Haunted Glade at Balmeanach A Haunted Glade at Balmeanach |

|

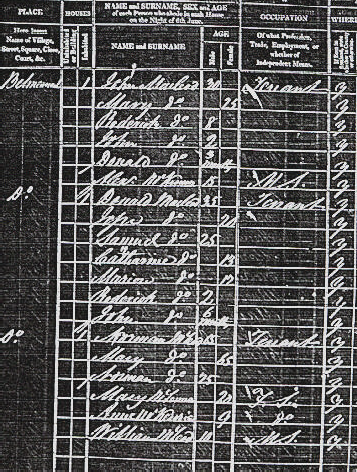

A Page of the 1841 Census A Page of the 1841 Census |

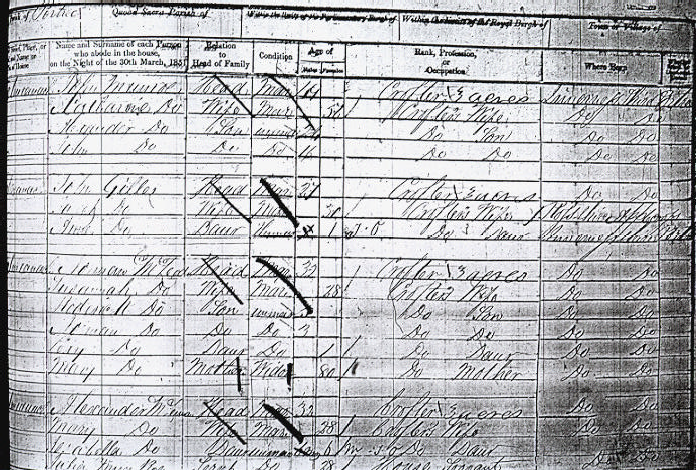

A Page of the 1851 Census A Page of the 1851 Census |

| The diagonal strikes were made in 1861 to denote adults who were no longer there. They had died or had moved from Raasay, mostly to Australia. |

|

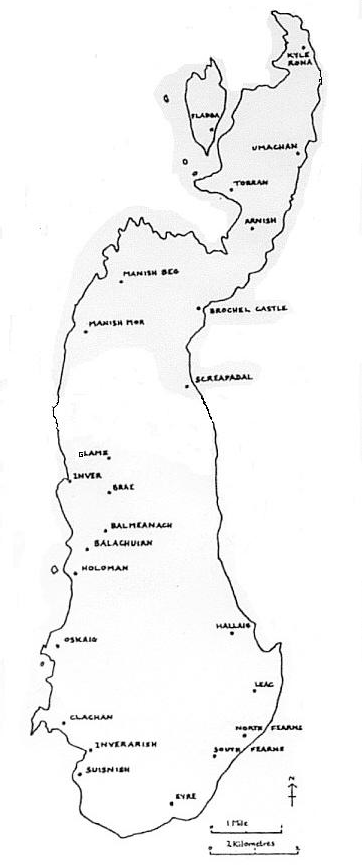

| A map of Raasay from Richard Sharpe’s RAASAY – A Study in Island History. |

On 6 June 1854 the Steamer Chevalier called in at Raasay and took aboard emigrants for Australia. This was not the first consignment of Raasay people to depart for foreign shores, but it was the largest. The Chevalier took the Raasay emigrants to Liverpool, where the Edward Johnston awaited to take them on the long voyage to Australia. The Edward Johnston was a sailing ship of 998 tons and carried 356 emigrants, including 132 from the Isle of Raasay and 183 from the Isle of Skye. She left Liverpool on 17 June and arrived at Portland, Victoria, Australia on 3 September 1854. It was a comparatively good trip and only two of the emigrants died en route, both very young children.

Some indication of the trauma surely connected with that June day of departure can be gleaned from a report in the Illustrated London News of an earlier clearance from Harris. In the edition of 30 December 1852 their reporter pontificated as follows:

Coarse and rugged as is the country, and wretched as is the state of the inhabitants, their affection for it seems intense. The scene on getting the creatures on board was really very affecting. The Commissioners, so far as is practicable, did not divide families but made a point of taking out the whole, even when the age of some of them rendered them very unfit subjects for emigration. Notwithstanding this, however, the attachment of some of the more elderly to their native soil was so strong that they could not be induced to leave it, and in their case the parting scene was most pathetic. Aged sires about to be severed from those with whom they had traversed the weary pilgrimage of time, were here and there bathed in tears, and bidding a last sad farewell. The youths, whose recollections of the past had awakened in their bosoms the pleasing associations of scenes never to be enacted, were here and there seen parting with their companions, and lamenting over the hard fate that rendered necessary a severance from those with whom they had been brought up and passed their happiest years.

Another account is given by a Miss I. L. Bird of Wyton Rectory, Huntingdon, England. In July 1852 she sailed from Portree on Skye to Oban on the Scottish mainland with about 300 Skye emigrants on their way to Geelong in the Georgiana. She wrote:

During a passage of twenty two hours, exposed as they were to a broiling July sun, and enduring all the miseries of sea-sickness, I never heard one murmuring word. They expressed great gratitude to the Emigration Commissioners, and almost overwhelmed the agent who accompanied them, with their expressions of thankfulness for the bread and butter which was served out to them. It required all my convictions of the necessity and mercy of such a measure, to balance the sorrow with which I regarded the exodus of such a simple and religious population from our shores. The misery must indeed be felt to be hopeless, which makes a people, whose local attachments are so strong, welcome a distant exile with gratitude. The Coollen (sic) mountains were in sight for several hours of our passage: but when we rounded Ardnamurchan Point, the emigrants saw the sun for the last time glitter upon their splintered peaks, and one prolonged and dismal wail rose from all parts of the vessel: and fathers and mothers held up their infant children to take a last view of the mountains of their fatherland, which in a few minutes faded from their view forever.

A much later but more perceptive insight into the Clearances is given by Christine Marion Fraser in her Green Are My Mountains, published in 1990:

I wasn’t surprised to learn of the Highland and Island clearances that had taken place on this part of the island, for I sensed the sadness, the desolation and despair the very first time I came across that moor, knowing nothing of these heartless evictions.

Today there is little to tell of that time, only one or two croft houses dotted about, deserted, roofless, only the sough of the wind keening through empty windows, only the sheep huddling in grassy spaces that had once sheltered men, women and children, laughing and talking by their peat fire blaze, never dreaming that one day they would be herded from their homes like cattle and forced to leave the land of their birth, forced to forsake their roots and their beloved glens and bens.

|

|

| Waterlily at Balmeanach |

Sad, sad is their Scotland now, eternally weeping for the children gone from their shores, leaving behind a country that is lost and bewildered and poorly managed by people who have never understood her, nor ever will, for they have never known her earth and her hills and the strange beauty of blood and ties that never die, no matter the years and the distance that separates the exiles from their homeland.

To go back to the lives of Norman and Susan on Raasay: shown earlier are copies of extracts from the Scottish censuses taken on 7 June 1841 and 31 March 1851. The former was the first ever census conducted in Scotland; they have since taken place every ten years. In the 1841 census the ages of people over 14 were rounded to the nearest ‘5’ so generally, but not necessarily, the 1851 census was more accurate about ages. It also contained more data than the first one. In addition to the four families shown on the copied 1851 page, there was also at Balmeanach a family consisting of seven Gillies. In 1841 the hamlet of Balmeanach consisted of only three crofts, all rented by McLeods: John (who would have called himself and been known by everyone except government and church officials as Iain), Donald (Domhnall) and Norman (Tormod). Our Norman who was ‘cleared’ on the Edward Johnston in 1854 is the 25 year old living in 1841 with an older Norman and Mary. In 1851 old Mary is described as a Widow and as our Norman’s mother. However, his death certificate (for which his son Ruairidh was the informant) states that Norman’s father was Roderick McLeod and his mother Ann McKenzie.

Because the oldest sons of John, Donald and Norman McLeod (all living at Balmeanach in 1841) were called Roderick, it at first seemed a pretty safe bet that John, Donald and Norman were all brothers who, in the Celtic tradition, had named their first-born sons after their father. I have not yet discovered the names of John’s parents, but I have found that Donald emigrated to New South Wales in 1852 on the John Gray and that he gave his parents’ names as John and Catherine. An interesting thing about the family of Donald McLeod is that, though he has turned out not to be a brother of our Norman, we now know that his wife Jessie was a sister of Norman’s wife Susan. Both Jessie and Susan were the daughters of Kenneth Stewart and Ann Nicolson, who married on Skye in 1805.

In 1841 Susan, then aged 15, was living with her parents at the village of Valtos on the Isle of Skye. Kenneth and Ann had a very large family − at least 13 children and probably more. In addition to Susan and Jessie it is known that at least two of their other children came to Australia. They were Donald and Mary Stewart, who arrived on the New Zealander in 1853, Donald aged 30 and Mary aged 32. In 1866 Donald Stewart attended, and was an official witness to, the Branxholme funeral of his younger sister Susan.

The Sound of Raasay, with Skye dimly visible The Sound of Raasay, with Skye dimly visible |

|

The lady in the armchair is Rebecca Mackay, with whom Charlie and I have stayed on each of the two occasions we have visited Raasay. The first time was in 1990, and this Raasay story really starts on the Isle of Skye. We were driving around marvelling at the wondrous sights of Skye and, as is our wont, became lost. I realized we were off the track when I found that the one-lane road we had been carefully following had finished up in the backyard of a farmhouse.

As I attempted to drive out of the unknown farmer’s back yard, he drove into it. Naturally, he asked what we were doing there, and was told that we were two Australian sightseers who had lost our way. He was a nice fellow − he enquired if we were looking for our ancestors. I told him that I believed my ancestors came from either Skye or Raasay, but I wasn’t sure which. He was interested to learn what I did know about them, and I told him that my great-grandparents were Norman and Susan McLeod and that they had emigrated with their young family to Australia in 1854, on the Edward Johnston. “Och,” he said, “If they came from Raasay, I’ve a cousin who would know all about them. Her name’s Rebecca McKay and she knows everything about everyone who ever lived on Raasay.”

The nice Highland gentleman introduced himself to us as John Nicolson. He had grown up on Raasay and had written a book, I Remember. He had some copies in the boot of his car. It’s an interesting book, and we have an autographed copy.

After that pleasant encounter we spent a few more days on Skye and then travelled to Harris and Lewis. On first reaching Harris we contacted the Tourist Office there and arranged accommodation at our next intended Hebridean location, the Isle of Raasay. A booking was made for us with a Mrs Mackay who ran a ‘Bed and Breakfast’ establishment.

A few days later we caught a ferry back to Skye from Lewis, and from Skye another ferry to Raasay. We’d been given directions to Mrs Mackay’s residence when on Harris. They read “Drive off ferry and turn left. Left again past two telephone kiosks. Drive north to first cattle grid and house is beside cattlegrid.” It was as easy as it sounds.

When we arrived at our destination we were met by the charming lady pictured on the previous page. “Aah” she smilingly said. “You’ll be the two Australians who are seeking their ancestors. Well, take your bags inside and then come back out here to the porch. They lived just a wee way up the road. I have their records all spread out on this table, waiting for you.”

And she did − the entry for Norman, Susan, Ruairidh, young Norman, Lexy and Mary Ann on the HIES List for the Edward Johnston, plus copies of the 1841 and 1851 censuses for Balmeanach, which is only a couple of kilometres up the road from where Rebecca lives. She directed us later to the ruins of the crofter’s cottage they had left behind them. She is still our very good friend.

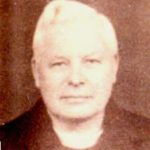

Rebecca’s mother was a McLeod and she is sure that she and I are related. Her basis for that belief is that she says I look very much like the Reverend James McLeod (Seamus an Achaidh), a Minister of the Free Church of Scotland, to whom she is certainly related.

|

|

| The Reverend James McLeod |

I guess he does look a bit like one of our mob. I would love to be related to Rebecca, and I wouldn’t mind being related to Seamus, because he is definitely related to Captain Malcolm McLeod, Tacksman of Eyre and Brae, mentioned at length in the earlier chapter.

A proven descent from Captain Malcolm would enable us to trace our ancestry back to Leod himself! It’s a relationship that might very well exist, but it is unlikely ever to be proven. Rebecca has told us that Raasay lore has it that Malcolm sired scores of ‘natural’ sons and daughters.

The old communal runrig system of farming has to some extent been re-introduced to Raasay. Much of the island (I’m not as clear on the details as I should be) is leased from the Government (now the Scottish Government!) by a co-operative formed by a group of Raasay farmers, one of whom is Rebecca’s now ex-husband Calum Don Mackay.

Calum Don surveys the scene Calum Don surveys the scene |

Shearing time on Raasay Shearing time on Raasay |

| Looks a lot like shearing time in the Western District, doesn’t it? |

A Magic Glade on Raasay A Magic Glade on Raasay |

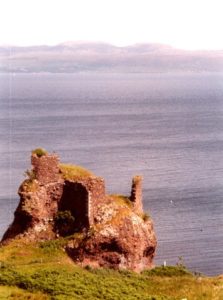

Brochel Castle, Raasay Brochel Castle, Raasay |

The Ruins of St Moluag’s Ancient Parish Church The Ruins of St Moluag’s Ancient Parish Church |

Celtic Cairn on Raasay Celtic Cairn on Raasay |

Pictish Symbol Stone on Raasay Pictish Symbol Stone on Raasay |

Celtic Cairns and Pictish Symbol Stones are not the only mysteries of Raasay. There is also the mystery of the origins of our Roderick McLeod. Who was he? Where did he come from. What did he do?

The only ‘name-relevant’ extant marriage record in all of Scotland for the period concerned is of a Roderick McLeod marrying an Annable McKenzie on 11 December 1816 in the Parish of Lochbroom, Ross-shire. Lochbroom is on the Scottish mainland, about opposite the Isle of Raasay. Another Lochbroom record shows that a Roderick McLeod was the father of a Norman McLeod who was christened on 13 April 1817. These could very possibly be our people. In those days Highlanders travelled from island to island and to and around the mainland much more frequently than we might imagine. It is quite conceivable that Roderick McLeod of Raasay travelled to Lochbroom and there found his love, Ann McKenzie. (Not that there was any great shortage of McKenzies on the Isle of Raasay.)

The fact that only one likely marriage record for Roderick and Ann now exists does not, however, mean that there weren’t once others. Many of the old Parish records have for one reason or another been lost or destroyed, particularly, it seems, for the Isle of Raasay where the Free Church of Scotland (which greatly distrusted the State) had its origin.

And what was the relationship between our Norman and the old Norman and Mary with whom he was living at Balmeanach in 1841? They were said to have been his parents; were they his grandparents? Was Roderick their son? It seems very likely that at least two of the children of the old Norman and Mary were emigrants to Australia. Their son (for sure) William and his wife Mary McLean raised a large family at Kilmore, and their daughter (very probably) Christina and her husband James McKenzie did likewise at nearby Romsey.

At the time of first writing the book “McLeods and Malseeds” I surmised that the photograph copied below was probably one of my great grandfather Norman, husband of Susan Stewart. It was also included in Vanda Savill’s The Great Swamp. It is a photo of an imposing figure of a man in a kilt, a man who looks very much like my grandfather Ruairidh. In Vanda’s book it was labelled Norman McLeod. The fact that it was so labelled indicates that someone did not think it to be a photo of Ruairidh. It certainly looks like him but the strong family resemblances possessed by the sons of other large McLeod families mean that this likeness is not totally conclusive. Ruairidh and his brother Norman were probably both “chips off the old block” and looked much like their father Norman.

The photo of the man in the kilt lent to me by Kevin MacLeod to reproduce was kept by him in an envelope on which faded letters spelled out Norman McLeod, Morven Park. I first assumed that the photo must be of Ruairidh’s brother Norman, whose Condah property was named Morven Park. It then occurred to me, however, that the writing on the envelope may well have referred to the person to whom the photo belonged rather than to the name of its subject.

My late sister Betty, reliable in all matters, clearly remembered a large, framed portrait of the man in the kilt hanging on a wall of the long narrow room called the lobby which ran across the front of Albanella. It seemed to me that a photograph of his younger brother would have been out of place as a prominent feature of the reception room of Ruairidh’s residence. If, however, the picture was of Ruairidh, or of his father Norman, it would have been a most appropriate place for it to be hung and also fitting that the younger brother have a postcard-sized copy of it.

Since writing “McLeods and Malseeds” I have seen the inscription by Peter Routledge on the back of a similar, but not quite identical, photo of “The Man in the Kilt”. It states quite clearly that the photo is of Peter’s grandfather (and Ruaridh’s younger brother) Norman McLeod. As well, Maryanne Martin has pointed out to me that the pioneer Norman McLeod, who died in 1868, was not likely to have had the “time, money, access or inclination” to be photographed in a studio. It is now my opinion that “The Man in the Kilt” is almost certainly my grandfather Ruaridh’s brother Norman.

|